|

|

|

There are over 35,000 villages in Rajasthan

with varying population of between 100 and 5,000 people, and 1,000 to

2,000 persons on an average. The village communities provide the basis for

all social life in Rural Rajasthan. This section will provide you

information about the lifestyle and social infrastructure of the rural

Rajasthan.

The colourful and picturesque costumes of Rajasthan reflect the people’s

joy of life and the desire to enliven their environment.

The men’s dress among the common people consists of a dhoti, an

untailored piece of cloth (about 4.5 metres X 4.5 metres), a bandia

angarkha or a full-sleeved, close-fitting, but buttonless vest and potia

or covering for the head. Among the well-to-do, the dhoti is a refined

handloom product with a coloured border. About the middle, the dhoti is

tied round the waist forming a waist-band. One of its ends passes between

the legs and is tucked in the waist-band behind, while the other is

gathered in pleats and tucked in at the navel.

On ceremonial occasions, the official class and the Rajput gentry use the

tight-fitting churidar pyjama, the kurta or a shirt (usually made of

muslin without collar or cuff) and either an achkan or a lamba angarkha

(long coat). The potia is replaced on such occasions by a turban, a

graceful and dignified headgear generally called pag, paga or pagri – a

fine piece

of cloth about 16.5 metres (18 yards) long and barely 0.2 metre (nine

inches) in width, embroidered at both ends and tied round the head in

various ways. Of the various styles of headgear current in Rajasthan, the

Marwari pagri or chonchdar pag, (beaked turban) deserves notice. The use

of a cotton or wool-len scarf round the neck or over the turban is also in

vogue.

Contact with Europeans in the last century brought into vogue the Jodhpuri

breeches. They represent a combination of riding breeches and military

overalls.

The dress of a Rajasthan woman consists of a ghagra of skirt, a kanchli of

half-sleeved bodice, an abbreviated blouse leaving the midriff uncovered,

and an orhni (mantle) which is about 2.2 metres (2˝ yards) in length. The

ghagra is a full skirt which may take as much as 36 metres (40 yards) of

cloth to make. The orhni is worn gracefully over the head and graped about

the entire figure.

Equally interesting is the traditional jewellery worn by Rajasthan woman

from head to foot. The anklets and heavy bracelets tinkle pleasantly with

the movement of the body. Intricately designed bangles adorn the arm.

Ivory bangles, white of tinted red, are worn by all married woman. Heavy

jhumkas (earrings) with inverted chhatri suspended like a bell at the

bottom decorate her ears, while kanthas or hasli of silver or gold

beautify the neck of a Rajasthan belle. The borla or sheesh phool, a round

boss, adorns the hair over the forehead and looks most attractive.

The pictorial art of Rajasthan, with is theme of love and devotion, is of

universal appeal. It reflects the emotional life of the people and has

kept close to their poetry, music, drama and religion. Spread over a long

span of time – 16th to 19th centuries – it has three distinct phases in

its development.

With a freshness and directness of treatment, appropriate to a young

movement, early Rajasthan painters broke away from the worn-out tradition

of the illuminated Jain manuscripts of 14th and 15th century Gujarat.

Their spiritual impulse came from the Vaishnava revival in the from of the

Krishna cult. Thus, the early Rajasthan paintings depict incidents from

the life of Lord Krishna. Scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata,

the seasons (Baramasa), ballads and romantic poetry, are depicted with an

exuberant joy of life. A recurrent subject is the pictorial representation

of musical modes, the Ragmalas. The sentiment of love (sringar rasa) is

expressed throught Radha and Krishna typifying the eternal motif of Man

and Woman.

Rajasthan artists make use of brilliant colours rendered with tempere

effect. The women in Rajasthan miniatures are true to the Indian ideal of

feminine beauty-large lotus eyes, flowing tresses, firm breasts, slender

waist and rosy hands – and they reflect the heart of a Hindu woman with

all its devotion and emotional intensity.

By 1565, the Mughul school of miniature painting had established itself at

the court of Akbar the Great and begun to radiate its influence. The art

of Rajasthan was influenced by the technique of the court painters. Thus,

Rajasthan’s Ragmala paintings of 17th and 18th centuries show far greater

elegance in the treatment of the line and sophistication in colouring than

those of the earlier period. In the 18th century, Rajput chiefs began to

patronize art and their capitals, namely, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Bikaner,

Kishangarh, Bundi and Kotah became active centres of painting. New themes,

began to be attempted. Representations of durbar scenes, hunting

expeditions and royal processions, and portraits of the royalty and

nobility give some idea of the court life of those times.

With the disintegration of the Mughul empire towards the end of the 18th

century, the indigenous tradition reasserted itself in Rajasthan painting.

Freed from the imperial yoke, the Rajput princes built sumptuous palaces

and decorated them with frescoes whose themes were taken either from the

Puranic lore or from the life of the court. The paintings of this period

bear inscriptions on the reverse and sometimes on the margin. These

inscriptions give the name of the king or the grandee portrayed and often

the date of the painting and the name of the artist. Portraits of horses,

elephants and dogs are also attempted.

Rajasthan art spread far beyond the territory of the modern State of

Rajasthan. It found a congenial home in the hill-states of the Himalayas

in the north, Bundelkhand in the east and Gujarat in the south-west. One

of its offshoots, the Kangra School, grew into a vigorous art of great

beauty. Its creations combine the inspiration of Rajasthan art with the

technique of Mughul miniatures. |

|

Villages in Rural

Rajasthan |

|

The villages are small communities which

are also known as the peasant society. In a defined geographical

area, a few dozen to hundred of families live in residential

clusters surrounded by agricultural and pasture land. Such villages

take their name from those of important deities, or of founder or

ancestor, or even on the basis of the area's geographical or social

characteristics. The villages can be spotted from highways to which

they are usually connected by narrow roads. From the distance, old,

large trees and cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats, camels, and other

domestic animals can be seen. Villages are often located near

village ponds or talabs that provide the source of water for cattle,

people and irrigation. Most of the houses in the villages are

connected to each other through a network of winding, kuchcha

lanes. |

|

The principal road, which may or may not be metallic, usually ends at some

central point of the village. The typical village home has a compound

marked by mud walls or tree branches, and is entered through a gateway

that leads to the open courtyard where men meet, and cattle may be seen.

The doors of the houses open on to the road, and on both sides of the door

there are small chabutras or platforms where people sit, children play,

and women discuss the day-to-day matters that affect their lives. Village

communities tend to live in joint families due to their work of

agricultural ploughing, irrigation, harvesting, selling. For organizing

weddings, death rituals, betrothal and other festive ceremonies, people

stay in touch, visit other villages, convey messages, and discuss daily

matters.

More.... |

|

|

People of Rural Rajasthan |

|

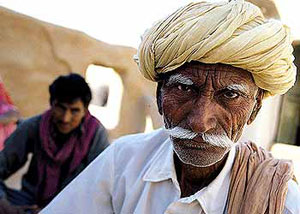

The villagers of

Rural Rajasthan are friendly and helpful, but wary of strangers. Men

and women never mix or talk in public except for business.

Amusements for the people are in plenty but are enjoyed in

segregated groups. In temples, small fortress, or at tea shops, the

people sit and exchange information, or merely pass time. On the

occasion of a baby’s arrival, a betrothal, or a wedding, women

gather in groups, dress beautifully and sing in a chorus for hours,

with the accompaniment of the dholak (small drum). Almost all

villagers in the rural Rajasthan are multi-caste. Traditionally,

there is one or few families of the Rajput caste who usually have

larger land holdings. They hold agriculture land and employ workers

from other caste groups.

|

|

|

A few

Brahmin families in the village supervise ritual activities, work as

priests in temples, convey information about fasts and festivals,

and regulate the local calendar of festivals and social activities.

The priest chart the auspicious day and time for beginning a new

venture at home or in the field. The Brahmin priests are also the

village astrologers. Kumbhars make

earthen pots and serve the needs of their village. Carpenters are

required for making and maintaining agricultural implements. Various

craftsmen, puppeteers, singers, dancers, drum beaters, record-keepers,

dyers, printers and other serving caste are also there in the village.

Child marriages are quite common and mass marriages take place on

auspicious occasions. The brides and grooms are often toddlers, and ride

in a wedding procession on horseback or camelback under the watchful gaze

of guardians. |

|

|

Folk people or

Tribes of Rural Rajasthan |

|

Nomads constitute about seven per cent of

the population of Rajasthan, and out of these, about one or two per

cent are non-pastoral or service nomads who comprise about two to

three hundred tribal groups with occupations like embroidery,

needlework, epic narrators, medicine sellers, fortune-tellers,

artisans, genealogists, dancers, singers, and hunters. Such nomads

visit villages in regular cycles to provide each community with their

services. Non-pastoral nomads offer more specialized goods and

services than any other culture area as in Rajasthan, villages are

located at greater distances from each other. At harvest time, various

nomads visit villages for providing important services. Members of

many families move to other villages or urban cities to earn a living.

The Rao-Bhats are family record keepers, and usually maintain the

records for a number of neighboring villages, on account of which they

need to travel frequently.

|

|

There are also mobile or gypsy castes who

inhabit villages for specific period of

time, providing a service while they camp

there. The Gadia Lohars, are ironsmiths who live and

travel in their own bullock carts, making and

mending iron implements for their

livelihood. The Kalbeliya families also move between

villages, camping in family groups wherever they stop for a few days. The Jats, Gujars, Yadavs and some other castes depend

entirely on agriculture. There are traditional caste families who work

on leather, weave cloth, grow vegetables, make ornaments, prepare

sweets, clean the village.

More.... |

|

|

Clothes

of People in Rural Rajasthan |

|

The colorful

head-wear (pugdi or turban) of men and the gaudy dresses of women

provide a wonderful contrast to the bleak environs of the state of

Rajasthan. In Rural Rajasthan, the rural women usually cover their

faces with a red or yellow colour odhni or dupatta and wear thick,

full-length ghaghara or skirt of the dark colour such as deep green

or dark blue with innumerable pleats and a blouse with colorful

designs. They adorn themselves with the heavy jewellery, earrings,

bracelets and rings made mainly of silver, which tinkles and jingles

when they grind grain, pound spices or draw water. The ornaments are

representative of certain social groups. The higher the caste group,

the lighter its use of dress (material and colours) and ornaments.

At the highest scale, fine fabrics and ornaments made of gold are

preferred. But in rural areas, silver ornaments are preferred. |

|

|

Silver

jewellery is usually heavier and uses

intricate, ethnic designs. Traditional

patterns are used for making necklaces,

earrings, bangles and anklets. Rings are

worn on fingers and on toes. A newly

married woman wear the boron on her head

all times, while the kankati or

waist-belt, and bangles of lac and glass

continue to enjoy vast patronage.

Weddings, the birth of children, and

festivals are great opportunities to find

women dressed in their finery. |

|

|

Music and Dance in Rural Rajasthan |

|

Music is the

lifeblood of village life in Rural Rajasthan. Songs are sung on

various occasions like childbirth, marriage, festivals, and during

their work in fields, or at home, when they take their cattle to the

pasture, or when they walk for long distances. Through music,

traditions are expressed and social systems are strengthened. No

festival is complete without music. Bhajans or devotional songs are

also sung. On various family rituals, neighbors and relatives are

invited to sing, especially at the time of Ratijaga, a ritual when

women have to stay awake through the night, singing songs devoted to

their ancestors and deities. Villagers also welcome and bid adieu to

their guests with songs. Dancing, too, is part of community culture

in Rural Rajasthan. In village life, group dances are preferred, and

men and women dance in separate groups.

|

|

In traditional

villages, the professional castes are

employed for the purpose of singing and

dancing for their patrons. One or more Dholi, the drum beater caste

is attached with a village. This family has rights and

obligations to serve the village with drum beating and singing. Mirasi,

Langa, Dadhi, Kalavant, Bhat, and Rao are various castes who sing, dance

and maintain family records of their patron castes. Some of the folk

musical instruments are often simple and even improvised from kitchen

utensils like the thali or metal platter, katori or metal bowls, cups,

fire tongs and the earthenware pot. The other instruments are jantar,

ravanhatha, tandoora, ektara, bhapang, kamaycha, while flutes, pungi-the

snake charmers' flutes, and dhols, dholaks, nagaras and changs (all drums)

are popular with folk musicians. Ravanahatta, a stringed instrument, is

played with a bow and is a forerunner of the western violin. Some of the

musicians roam villages singing songs about the adventures of ancient

Rajput heroes. These wandering minstrels are known as Bhats.

|

|

|

Religion in Rural Rajasthan |

|

In Rural

Rajasthan, each village has its own

deities (devtas) with shrines (devata

sthans) where the villagers go to pay

obeisance. In the summers, when most of

the land has a parched and barren look,

such religious spots are characterised by

a denser greenery and a small pond for

bathing, cooking and picnicking. These

spots also provide shelter for small

animals and birds. Most of the shrines are

located near the source of water since

cleansing of oneself is a necessary part

of the ritual of worship. Pathwari, the

goddess of the path, is found in almost

all villages in the form of a small

earthen or stone square structure which is

worshipped whenever a person undertakes a

pilgrimage. There are other mother

goddesses before whom the villagers pray

for shelter, nourishment and protection

from disease. The Bhairuji is a powerful

deity who looks after the interests of the

people of the village. Bhairuji's shrines

are rarely in the form of a temple, and

only a stone platform is there. Sagasji is

another local deity who offers protection

to harvests and animal life. Generally,

Sagasji is propitiated on the boundary of

a farm, or near an irrigation well.

Regional heroes such as Deo-Narayanji,

Gogaji, Tejaji and Ramdevji are worshipped

in villages. Some other gods which are

worshipped in the temples in Rural

Rajasthan include Lord Shiva, Krishna,

Ram, Lord Ganesh and other incarnations of

Vishnu. In villages where Muslim families

have their homes, a mosque or a roadside

shrine of Pir Baba can also be found. In a

cluster of villages, one deity is usually

more powerful or popular for a particular

power or authority. The shrines and trees

are not only protected, but also regarded

as sacred groves. |

|

Fairs and Festivals in Rural Rajasthan |

|

Fairs and festivals lend

vibrancy to village life in rural Rajasthan. A large number of fairs are

organized in rural areas, and the rural population gather in large number

to attend such fairs. Such fairs have a mixed commercial and religious

aspect. For example, in the Pushkar fair, cattle and camel trading is

combined with the annual pilgrimage to the Brahma temple and Pushkar lake

for ritual bathing and worship. Villagers use such opportunities for

buying the things they do not usually get in and around their villages. In

the local fairs, the villagers buy simple implements, tools, utensils and

jewellery. Women buy dresses, mirrors, utensils, printed bed sheets,

bangles and toys for children. Festivals are celebrated as family or

community events. During Gangaur festival in the month of Chaitra

(March-April),

|

|

|

young unmarried

girls and those recently married visit

gardens in groups to bring flowers and

water pitchers and worship Gangaur or

Gauri Mata, the mother goddess, for being

blessed with an ideal husband, or for the

husband's well-being for about fifteen

days. Teej is celebrated in the rainy

season, a festival again for women, and

linked with marital celebrations. Amavasya,

the dark night, is considered inauspicious

by villagers who neither buy nor sell

anything on that day. Craftsmen, milkmen,

farmers and vegetable sellers do not work

on that day. On festivals such as Holi,

Diwali and Rakhi, rice and sweets are

cooked as consecrated offerings for the

gods. The tradition of telling stories on

those days when people observe fasts is

also popular in rural Rajasthan. During

such festivals, the women from the same

neighborhood tend to worship together, and

recount tales related with the fast.

Remembering myths and history is one way

of transmitting culture from one

generation to the next.

|

|

|

Cuisine of Rural Rajasthan |

|

The cuisine of villagers in

Rural Rajasthan consists of one or two vegetables and rotis (breads)

on which ghee (clarified butter) is used. Rotis of wheat, maize, and

millets (bajra) are made. Rural cooking is a simple exercise, and

done by the women of the house. There are no sweet shops in the

Villages, and only milk and milk products like butter, buttermilk

and curds are consumed. Many communities are vegetarian, and in most

hamlets, these two frugal meals of Roti and Milk provide their basic

diet. Chai (tea) is prepared early in the morning, and in the

afternoon or evening, and whenever there are visitors. It is usually

strong, milky and very sweet. |

|

|

Industries in Rural Rajasthan |

|

In Rural Rajasthan, agriculture and allied

industrial sectors employ about 89.5% of the labour. Jowar and Bajra

are important food grains grown in Rajasthan. Some of the roads or

lanes are connected with the farms, and people are associated with

some form of agrarian activity. A few prosperous farmers have

substantial agricultural holdings to manage wells or canals. The

middle level agriculturists tend to work on their own farms, while

those whose holdings are small or not arable enough find

opportunities to work outside their farms. Tractors, threshers and

irrigation pumps have shortened the manual work of most men on their

lands. Most of the villagers now have enough electricity to run

irrigation pumps. Sheep grazing is a common sight, and sometimes

girls take up this job. Wool, dyeing and hand-painting are the main

industries. Bandhani prints are the main example. Today, with

improved means of transportation, fresh vegetables have arrived at

the doorstep of even the most remote village which was even not

possible a decade ago.

Infrastructure of Rural Rajasthan

Agricultural activity is looked after and helped by government

departments. The cooperative banks provide loans and new varieties

of seeds, chemical fertilizers, medicines and seedlings. Most of the

villagers now have enough electricity to run irrigation pumps. |

|

|

Drinking

water facilities have been created in

almost all villages. Dispensaries and

medicines are not far off from villages.

Roads have joined villages with towns, and

regular buses and other means of transport

are available. Television sets and radios

are providing the basis for more changes

in rural life. Telephonic communications

link the smallest village with the world

outside. Cinema and newspapers are

reaching across to them. But even as

changes are being brought about in their

lifestyles, the villages continue to be

the heart and soul of Rajasthan. |

|

|

Villages to Visit |

|

There are many villages in Rajasthan which can be visited. Some of these

villages are located in the Shekhawati region, around Jaisalmer, Udaipur

and Bikaner. The villages of Rajasthan are a classic way of exploring the

arduous life of Rajasthani folks who lives on the stubborn pulse of

nature. If you want to experience the true essence of Rajasthani village

life and that too from a close quarter, then you can stay in the rugged

huts of the village people and also enjoy their unique lifestyle with

delicious village cuisine.

More.... |

|

|

|

Rural

Rajasthan |

|

Villages in Rural Rajasthan

||

Villages to Visit in Rural

Rajasthan ||

Folk Tribes of Rural

Rajasthan ||

Arts of Rural Rajasthan

||

Art and craft of Rural

Rajasthan ||

Rural Rajasthan Tour

||

Rural Rajasthan Tour

Packages |

|