Kalibangan - the largest

prehistoric site in Rajasthan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kalibangan - the largest prehistoric site in Rajasthan |

|

Just as scholars and laymen all

over India, have heard of Mohenjodaro, so scholars and laymen, particularly in

Rajasthan, should have heard or read about Kalibangan.

Kalibangan is perhaps the largest prehistoric site in Northern Rajasthan. It

is situated in the Ganganagar District (now Hanumangarh), which was formerly a

part of the state of Bikaner. It is easily approachable from Hanumangarh

Railway Station on the Delhi- Bikaner line.

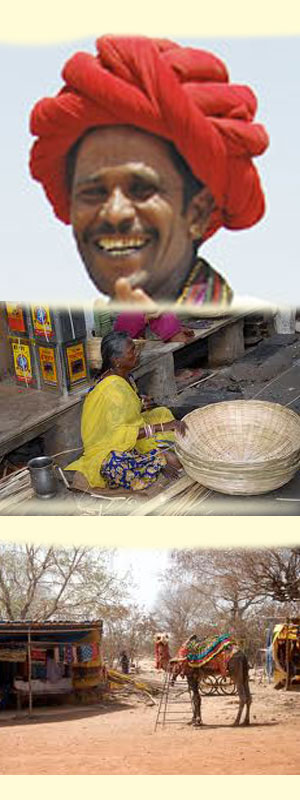

People of Rajasthan and particularly the residents of Jodhpur, Jaipur and

Bikaner know that this region is practically a desert, with occasional thorny

bushes of babul and thor. In this surroundings, a village or a town with

whitewashed mud houses, or timbas (tillas) – small mounds or hillock, strike

the eye immediately. While many of these tillas are nothing but sand-dunes,

some of these, as Rangmahal on Kalibangan are littered with innumerable

potsherds. Because these potsherds were originally red or even bright red,

these mounds even now after hundreds or thousands of years appear reddish.

Particularly this is so at Rangmahal.

Normally no one cares for or looks at these potsherds, certainly not the

caravan driver who passes by these tillas while carrying goods to and fro,

from distant towns and cities. But to an archaeologist these potsherds are

like open books. All these potsherds speak. Perhaps each potsherd has some

story to relate. You may wonder “how”. The reason is simple. Though the shapes

of the pots to which these potsherds belong are rarely intact, still the

potsherds are not dead. It is one of the wonders of nature that once a clay

pot is given some color, or naturally painted with some designs and then

fired, neither the color nor the design goes, though the pot or its pieces may

be exposed to the sun and rain and even used for hundreds of years. It is this

Nature’s secret that archaeologists discovered some 150 years ago. For by

carefully studying potsherds and intact pots if available, an archaeologist

can gradually tell how old the pot is, he can also say by further study and by

piecing together broken parts of the one and the same pot, what the original

shape was, and what part it played in the life of the person who possessed it.

It is the peculiar feature – almost total indestructibility – of pottery –

that is one of the main clues which an archaeologist looks for whole searching

for bygone cultures and civilizations. Hence Shri Amalananda Ghosh during his

exploration of the valleys of the Ghaggar, the ancient Saraswati and the

Drishadvati primarily looked for collected potsherds. Of course he was not the

first scholar to do so. Before him Shri Aurel Stein had done so for that part

of the Ghaggar which flows into the Bahawalpur District of Pakistan. Stein

thus had discovered numerous ancient sites. In some of these, he had

discovered the kind of pottery which had been discovered previously at

MohenJodaro and numerous other sites in Sind. Ghosh did exactly what Stein had

done, but being more experienced and well acquainted with the Harappa or the

Indus Civilization he noticed that three or four different kinds of potteries

were found littered over these tillas in the Bikaner State. While those

similar to or identical with that of the Indus Civilization can be easily

assigned to the Indus Civilization, others belonged to different cultures. The

pottery found at Sothi and other sites in and around the present town was

designated as “Sothi”. While another – found at Rang Mahal was called “Rang

Mahal Culture.” Because of its bright red color and painting, Rang Mahal

appeared promising. It was certainly new. But when it was excavated by a

Swedish Expedition, it was found to belong to the early Historical period, to

the period of the Kushan ruler of Northern India, including Rajasthan. So when

the Archaeological survey of India though of examining of pursuing Ghosh’s

discoveries they took up the mounds at or near Kalibanga. For here had been

found potsherds and chert knife blades indicative of the existence of the

Indus Civilization and also another culture or civilization called the Sothi

Culture by Ghosh.

And as rightly anticipated by Ghosh, several years of excavations at

Kalibangan by Prof. B.B. Lal and Shri B.K. Thapar have brought to light the

existence of a fairly extensive town of the Indus Civilization Harappan

Culture, and also the earlier existence of a town to the pre- Indus or Sothi

culture. However, as it is the practice with archaeologists, these Sothi or

pre - Indus culture have been designate respectively Harappan cultures

respectively.

The ancient habitations was spread over an area of a quarter of a square

kilometer, and from the beginning consisted of two closely-knit but distinct

mounds, an eastern and a western mound. These form a prominent feature of the

landscape with their slopes strewn with dark brown nodules, mud-bricks, and

numerous potsherds. No traveler in this desert, whether he be an archaeologist

or not, could but be struck by this feature of the landscape with their slopes

strewn with dark brown nodules, mud – brick, and numerous potsherds. No

traveler in this desert, whether he be an archaeologist or not, could but be

struck by this feature for these are so conspicuous among the masses of sand

dunes on the west, east and south and the green fields on the north; the

latter as a result of irrigation. |

|

|

|

|

Fortification |

|

This pre – Harappan settlement was protected

by a mudbrick fortification. When first built it was about 6

feet (1.90m) wide, but later the width of the wall was almost

doubled. It varies between 3.70 and 4.10m. the brick size

however remained the same. No corner angles of these walls have

been found. The north – south distance of the fortified area

measures approximately 250 m. The necessity of such an increase

indicates that the inhabitants felt insecure with a wall that

was only 6 feet wide and hence made it up to nearly 12 feet.

This is certainly a good thickness for a fortification wall at

this period, for it had to withstand only such missiles as stone

or copper-tipped arrows and clay or stone sling balls. Whether

this wall could be easily scaled or not cannot be said, there is

no means of knowing its height, since the later people – the

Harappans in our present knowledge had to break it or remake it

to sit their requirements.

What is important is that the traces of a fortification wall

have survived. We were told by Marshall some 40 years ago that

the non-violent people. Then came Sir Mortimer Wheeler who was

the first to identify a defense wall at Harappa and then later

at Mohenjodaro. This discovery made him propound his famous

theory that the Aryans destroyed the Indus Civilization, for he

saw in indra, the Purandara, one who destroyed “walled”

“fortified cities.”

Now with the discovery of fortification at Kalibangan, and also

at Kot Dijji in Sind, where the mud-brick wall has a plinth of

stone rubbles, the whole problem of fortification takes a

different turn.

The least we can say is that the Harappans were not the first to

have fortified cities in Sind and Rajasthan. And hence the

question of Aryans along being “the Purandaras” does not arise.

These might as well be the Harappans, who at Gumla destroyed the

pre-Harappan habitation.

Again, they were not the first to introduce wheeled conveyance

and metal tools/weapons, in these regions, for these were also

known to the pre-Harappans. But what the latter did not have was

the first access to the flint quarries of Sukkur and Rohri so

that their tools for daily use in the house for cutting,

slicing, and piercing had to be made from (presumably local)

material such as agate, chalcedony and carnelian. These tools

are in now way different from the microliths made by the Bagor

and Tilwara people, except that at Kalibangan we have mostly

straight-sided blades including serrated and banked and fewer

lunates, trapezes and such geometric shapes. This small

difference is significant, indicating that man no longer needed

and made compound tools like the sickle and harpoon and the

arrow-head with stone tips, but utilized (probably) copper tools

instead.

|

|

|

|

|

Pottery |

|

However, the most striking difference between the pre – Harappan

and the Harappan, which is of utmost importance to an

archaeologist, is pottery. The Harappan pottery is bright or

dark red and uniformly sturdy, and so well baked that no part of

the core remains yellowish or blackish showing imperfect firing.

This is not the case with the pre-Harappan pottery. The latter

is pinkish, comparatively thinner, and not so well baked as the

former. Some of it is distinctly carelessly made. One of its

varieties, though well – potted, has its outer surface,

particularly the lower part; roughened or rusticated (this is

also seen at Ahar). Still another variety, represented mainly by

basins, is decorated all over by obtusely incised patterns on

the outside.

Not only the fabric and most of the decorative patterns, but the

forms of the pre-Harappan pottery are strikingly different from

the Harappan. While the graceful painted Harappan vase, the

goblet and the cylindrical perforated vessel, and the variety of

footed dishes or foot-stands are conspicuous by their absence,

present are some six to eight types of small and medium-sized

vessels. And amongst these, the most noteworthy is a small footed

cup. This and its likes remind us on the one hand of the earlier

Iranian goblets from Sialk and Hissar, and on the other the

goblets or footed cups from Navdatoli on the Narmada. |

|

|

|

|

New Features |

|

Though in a general

way all this conforms to what we know of the Indus Civilization,

Kalibangan has revealed certain new features.

First there are the usual two habitations. One is the so-called

“Citadel” on the western side located on the earlier pre –

Harappan settlement overlooking the ancient Saraswati. It is a

coincidence that in all the three sites – Harappa, Mohenjodaro

and Kalibangan, the citadel is located on the western side and

that on a previous habitation? The other is situating towards

the east, at a little distance from the first, rich on the sandy

plain. It appears now that both these – the “citadel” as well as

the “lower city” was enclosed by a separate mud-brick

fortification wall. Of the city fortification only the east west

wall running for nearly 230 feet (over 80 m.) has so far been

exposed. The north – south wall is not yet fully laid bare.

Within the city, so far five-north south and three east – west

roads, and a number of east – west running lanes have been

explored, showing how well – planned the city was. The roads and

streets were found to be clear of any intrusions from the

house-owners and squatters – a civic feature which is becoming

rare all over India today.

Whether there were too many carts moving in the streets or not

we do not know. But to avoid damage to the houses at street

comers, by the sudden turning of the cart, wooden fender posts

were provided, a few of which survive.

Rectangular platforms outside some of the houses seems to have

been made for two purposes. Either as outdoor rest-places, or

contrivances specially made for mounting over an animal’s back,

or rests for laborers carrying heavy load over their heads. |

|

|

|

|

Houses |

|

Such well laid out

streets were not metalled, except in the late phase of the city,

not were they provided with regular drains, as in Harappan

cities. However, the houses had drains made of either wood

scooped out in the shape of ‘U’, or more often with baked

bricks. These drains emptied themselves in the soakage jars

embedded in the street floor. It is observed that each house

opened or had a frontage on at least two or three streets, as in

Chandigarh, for instance. Normally, only one, the corner house,

can have such a frontage, but others at the most two, a front

and a back one, that too if there is only a single row of houses

in a street or a lane. In the Harappan phase at Kalibangan there

was only a single row of houses in each street, and this again,

divided into several small blocks, so that many open to so much

light and air in a region like N. Rajashtan? Or was it after the

current fashion, as today in Chandigarh? Even internally the

houses were well provided with light and air, for they were

built on the Chatussala principle, that is, there was a central

courtyard, at times provided with a well and six or seven rooms

on its three sides. There is some evidence to say that these

earliest houses in Kalibangan were storeyed, for in one house

were found traces of a preserved stairway.

The roofs of these houses were probably flat. As today in

Kalibangan and many villages in Rajasthan, the houses were built

of mud-bricks. The size of which was 20x15x7½. cm. That is the

length was twice the thickness, the proportion being 4:2:1.

However, the Harappans of Rajasthan were judicious, for they

have consistently used baked bricks in doorsills, wells and

drains, all places where the wear and the tear was much, and the

structures liable to be damaged if baked bricks were not used.

This common sense is again witnessed in the way the flooring of

houses are made. Unlike Mohen-jo-daro and Harappa the floors

were made firm by ramming (called Koba), and sometimes capped

additionally with mud bricks or terracotta nodules.

However, in one case, the floor is found paved with tiles,

bearing the typical intersecting design of circles. Exactly

similar design occurs at Kot Diji in what is called a “bath

tub”. While there is no doubt about the existence of this design

in the tub-like large vessel at Kot Diji, it should be

ascertained, if not already done, whether at Kalibangan it is

real flooring or too is a part of a tub. Anyway, this is a most

interesting feature, which does not seem to be merely

ornamental, but perhaps of some religious significance, or else

some other design would have been preferred. For we know this

was a favorite design with the Harappans, and occurs on the

graceful vase.

The Bikaner Harappans thus show considerable originality even in

the make up or construction of their house. This is further

illustrated by three other features. All these are seen in what

is called the “Citadel Mound”. |

|

|

|

|

Fortification |

|

The exposed fortification in this mound makes it look roughly

like a parallelogram on plan, exactly as at Harappa, that at

Mohenjodaro is not fully exposed, but would probably be of the

same shape. This was divided into two almost equal halve. Each

half may be described as a rhomb. Again each of this rhomb was

enclosed by a fortification wall. The width of th8is wall was

quite large, as much as 7 m. (about 20 feet) at places, the

minimum being 3 m. (10 feet). This was further strengthened at

intervals with rectangular salient (projections) and towers. The

wall, it would appear was built in two phases or twice, for

initially very large bricks measuring 40x20x10 cm. were used in

its construction. Later the normal sized bricks (30x5x7½ cm.),

used in civic houses were preferred. |

|

|

|

|

Platform |

|

The southern rhomb is found to contain five or six platforms of

mud or mud bricks each separate from the other, and different in

size, so that the space (passage) between the two platforms is

never uniform. Now here are these platforms connected with the

fortification wall. Access to these platforms had to be by a

flight of steps, which rise from the passage between the

platforms. Further the passage fronting the steps was paved.

These mud or mud-brick platforms seem to be quite different from

the platform at Lothal, Harappa and Mohen-jo-daro, for instance,

the latter were largely built for protecting the superstructures

from recurring floods. But at Kalibangan they seem to have a

religious function, though this cannot be ascertained, for

except in one case the superstructures have disappeared. Or is

(was) it because it had by this time become a custom, convention

or fashion to build the citadel on artificial mud or mud-brick

hillock? |

|

|

|

|

Sacrificial Pits (?) |

|

In the one surviving example was found a rectangular pit (1 x

1.25 m.) lined with baked bricks. This Kunda contained bones of

a bovine and antlers, perhaps a sacrifice was performed. This

suggestion is strengthened by the fact that adjoining the Kunda

was found a well and a “fire-altar”. |

|

|

|

|

Fire Altars |

|

A

row of such fire-altars was noticed on another platform and also

in many houses in the “ Lower city”. These “fire-altars”

invariably consist of shallow pits, oval or rectangular plan.

Fire was made and put out in situ (that is there and then), as

proved by lumps of charcoal in the open part of the pit. In the

center of the pit was found a cylindrical or rectangular

(sun-dried or pre-fired) brick. Around or near about were place

flat, triangular or circular terracotta pieces, known hitherto

as “terracotta cakes.” In a recent article it is said that

towards the end of the Harappan settlement this practice was

being gradually abandoned because the Saraswati was losing its

water to the Yamuna, the fire-altars were poorly equipped – only

with one centrally placed brick on edge in a small pit.

Such a “fire-altar” has also been noticed by Casal at Amri, and

something similar, but perhaps not identical, was found by Rao

at Lothal. Perhaps such fire-altars also existed at Harappa and

Mohen-jo-daro, but were missed in mass digging and have only

been revealed in slow, careful excavation.

That here in this platformed, well fortified enclosure we have

first traces of a religious building with houses for its priests

on the site which is also borne out by the fact that no barge,

broad streets have been so far found within the citadel. In

fact, there is no room for any vehicular traffic. So we have to

presume that either every-body walked, or some people – like the

priests and the like or the ruler – were carried in palan –

quins. The general public could go to these platforms from the

southern side through a stairway which ran along the outer face

of the fortification wall between the two centrally located

salient. A similar arrangement was made for the residents in the

northern half of the “Citadel”.

At all the three sites, these citadels are built over a little

higher ground, which at Harappa and Kalibangan is proved not to

be quite natural but due to the remains of an earlier

habitation. However, the elevation was further raised by mud or

mud – brick platforms. And this at Harappa and Mohen – jo – daro

(and Lothal) is explained as a precaution against recurring

floods. But at Kalibangan there is (so far) no evidence of a

flood, and again the platform are on separate block with paved

flooring in the passage. Further the fire-altar-like structure

and the sacrificial kunda on these platforms make the excavators

feel (and I agree with them) that these are truly religious

structures. Did they have a similar function at Mohen-jo-daro

and Harappa? Or there was the real need of a mud-brick platform

as a protection against floods, and this functional feature was

later mechanically copied at Kalibangan?

The smaller, portable objects at least testify once again to the

rich and comfortable life which we now associate with the

Harappans. A varied and beautiful pottery (its manifold uses for

eating, drinking, storing etc. could be imagined if the numerous

platters, dishes and other vessels found intact in a grave are

drawn function-wise), ornaments, beads and bangles – in shell,

terracotta, semi – precious stones and faience, and some in

gold, weights and measures (one in graduated scale as at Lothal),

the undeciphered seals including one cylinder seal with half

human and half animal figures on it, recalling Sumerian contact

and features, and above all, exquisite figure sculpture in the

round of a charging bull. |

|

|

|

|

Religion |

|

There is nothing specific to tell us about

the Harappan religion except the so called fire-altars and the

Kunda and an oblong terracotta cake, incised on both sides with

a figures reminds once again of the figure in gold in Hissar

III, and a painting on a pot at Kot Diji from the junction

layers. The incised figure seems extent we are familiar with a

horn-headed deity from the famous Pasupati-like seal. But there

the horns are not quite clear, and hence some scholars doubt it

identification. But in the Kalibangan figure there is no room

for doubt. And this as shown here can be derived from the

mouflon (or wild mountain sheep) head in gold form Hissar in

Iran through the painting of a bullas head on a pot at Kot Diji

in Sind, and also at Gumla and Burzahom. |

|

|

|

|

Food |

|

The Kalibangan Harappans were both vegetarian

and non-vegetarian. Wheat and barley they must have eaten,

though so far only traces of barley have been fond. Among the

animals they knew and probably cooked for food the largest

percentage is that of humped cattle (cow/bull), then Indian

buffalo, pig, arasingha, elephant, ass (domesticated) rhinoceros

and camel. The camel is again important, proving its antiquity

in this region (sind and Rajasthan). |

|

|

|

|

Burial Methods |

|

By and large the Kalibangan Harappans buried the dead, as at

west south west of the citadel has been found, on the present

flood plain of the river. Not only this cemetery sheds some

light on the different burial practices current at Kalibangan,

but the varying provision of grave goods, and the construction

of the graves enlightens us about the social stratification

prevalent in the city. So far three types of graves have been

found. In the first type, which seems to be fairly frequent, we

have an oblong pit dug into the ground. The dead body was laid

in the pit in an extended position with the head towards the

north and the feet towards the south. Then around the head were

arranged pots, dishes, platters, small water vessels, cups, but

not large storage jars, in one case numbering over seventy. This

illustrates that there was no fixed number of pts which one had

to provide for the dead. If one could afford, and probably

belonged to a higher social order, he could have a large number.

Besides pots, at times a copper mirror was placed near the head.

This is further proved by the fact that this particular grave ad

a lining of mud bricks on all the four sides, which were then

plastered with mud from inside.

In the second type the grave-pit was oval or circular on plan

and contained besides an urn, other pots including platters and

dishes-on-stand.

Here again the number varied from 4 to 29, depending upon the

wealth (and position) of the person. Again, besides pottery,

ornaments such as beads, shell bangles and objects of steatite

were kept.

In the third variety, the grave-pit was rectangular or oval on

plan with the larger axis oriented north south, but curiously

contained no skeletal remains. Usually nothing but pottery was

found within these simple pits, though in one case a shell

bangle and a string of satellite disc beads and one of carnelian

were found.

This is the first time that burials without any human skeletal

remains have been found on a site of the Indus Civilization. But

the reason behind this non-occurrence is not easy to gauge. It

is because that there was the custom of cremation-cum-burial, so

that the body was burnt, and later only the ash and a few bones

were buried in the urn, or even these were not kept but thrown

in the river or sea, as some people do today? |

|

|

|

|

Trepanning |

|

Kalibangan has also provided a very

interesting example of ancient medical belief and surgery. In a

child’s skull were found six circular holes. These holes were

made while the child was alive, for the wounds made by these

holes have healed, that is the edges of the holes have nor

remained sharp, as when first cut. This practice of boring holes

in the head while alive is called trepanning, and was widely

current in prehistoric times in Europe, about 3,000 B.C., and

was still witnessed in some of the aboriginal tribes of Peru in

Central America. Trepanning was resorted to, it is believed, to

relieve headache, and alleviate inflammation of the mastoid

(conical) prominence in the temporal bone to which the muscles

are attached), and on the brain due to injury.

So far the only example of trepanning we had was from Langhnaj

in north Gujarat, Kalibangan (and Lothal) have provided two

more. These thus give a wide base to a belief and practice which

was current in Europe and Africa, some 4,000 years ago; exactly

the time is was prevalent in Western and Northern India,

including Gujarat, Sind and the Punjab.

The Kalibangan has given us considerable food for thought. Again

the paved road and flooring. These are new features not so far

met with at Mohen-jo-daro. But we must also note the absence of

certain well-known features, such as street-drains, and among

the portable smaller objects the complete absence of lingas,

yonis, and figurines of mother – goddesses. This is also a

feature of the Lothal (Saurashtra) Harappan, and thus underlines

the importance of Mohen-jo-daro and Harappa as “religious

capitals” as well.

In many respects then the Rajasthan Harappan has a distinct

individuality. It is not an exact copy of the Indus. Such a

regional variation is but natural, though it would be worth

inquiring who introduced or brought about this variation, viz.

the indigenous element in the population or because during

migration from the centre, the original features got lost or

changed. |

|

|