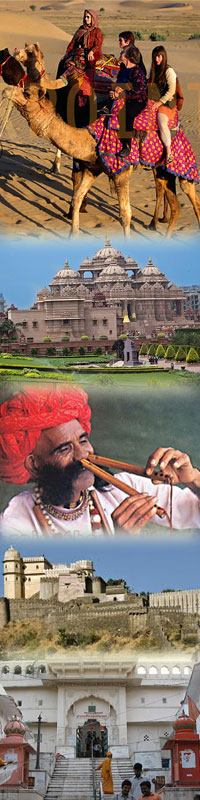

Sources of the History and

Culture of Rajasthan (From earliest times up to 1200 A.D.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources of the

History and Culture of Rajasthan (From earliest times up to 1200

A.D.) |

|

The advent of men in Rajasthan can claim greater antiquity than many other

regions of India. It is a geological fact that the Aravalli ranges are older

than the Himalayas. In ancient rive beds and natural rock – shelters of

Rajasthan have been discovered fairly early traces of human habitations.

Palaeoliths in abundance have been reported from Marwar and Mewar from Marwar

and Mewar regions of Rajasthan. Then we have a rich microlithic assemblage at

Bagor (Bhilwara District). In fact, the Chambal river-valley, Banas- Berach

basin, Luni river basin, rock-shelters of Viratnagar, ancient – lake sites,

old river – terraces, and several open air sites from different parts of

Rajasthan have yielded palacolithic and microlithic implements, indicating the

early activities of man in Rajasthan. Thereafter we find rich chalcolithic

cultures at Ahar (Udaipur), Ganeshwar (Sikar District) and Balathan (Udaipur

District). The recently excavated site of Balathal has presented the evidence

of a chalolithic village which is earliest (dated to 2500 B.C.) onto only in

Rajasthan, but in India.

The banks of the Saraswati river, which flowed through the western part of

Rajasthan, became the centers of two early and formative civilizations of

India viz. the Indus – Saraswati civilization and the Vedic civilization.

Kalibangan (Hanumangarh District) was an important center of Indus - Saraswati

civilization in Rajasthan. The Vedic literature mentions the Matsyas and the

Salvas as located near the river Saraswati and there is evidence to believe

that by the close of the Vedic age Rajasthan had become fully colonized by the

Vedic tribes. The relics of Painted Grey ware culture have been reported from

the dried- up beds of Saraswati and Drshadvati rivers. We also have evidence

of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) from Noh (Bharatpur), Jodhpur (Jaipur), Viratnagar

(Jaipur) and Sanari (Jhunjhunu). These sites represent the growth of Iron Age

in Rajasthan. |

|

|

|

|

Archaeological

Sources |

|

Inscription

The inscriptions serve as a very authentic evidence for the

reconstruction of the history and culture of Rajasthan. Not only

do they help us in building up the chronology and political

history on a firm basis; they also offer reliable pieces of

information about the contemporary life and conditions in

Rajasthan.

Listed below are some of the important inscriptions reported

from Rajasthan.

Barli Fragmentary Stone Inscription (5th or 4th century B.C.):

This fragmentary inscription was found in the temple of Bhilot

Mata, about a mile from the village Barli, situated about 36

miles southeast of Ajmer. The inscription is now preserved in

the Ajmer museum. It is engraved on a white stone which formed

part of a hexagonal pillar. The characters are Brahmi. The

language is Prakrit mixed with Sanskrit.

Coins

Coins, though they are small in size, sometimes play a big role

in illuminating history not known other sources. They also serve

as ancillary evidence for the history known from other sources.

Excavations and accidental findings have so far yielded

thousands of coins from different parts of Rajasthan.

The earliest coins reported from India are known as ‘punch

marked coins’ which are made of silver and are dated from c. 600

B.C. to 200 B. C. The punching devices of these coins have no

inscriptions; instead they have a number of symbols. A very big

hoard of punch- marked coins was discovered from Rairh (Tonk

District) in Rajasthan. This hoard consisted of 3075 punch –

marked coins of silver.

An another significant hoard from Rajasthan is that of Gupta

gold coins discovered at Bayana (Bharatpur District). It

consists of 1821 gold coins, which add to our knowledge of Gupta

period in general. This hoard has furnished valuable information

about Gupta currency in particular. It is also indicative of the

prosperous conditions prevalent in India during the Gupta

period. The artistic designs on these coins revel about the

aesthetic sense of the society. Five Gupta coins of silver from

Ajmer discovered by Dr. G.H. Ojha and one silver coin of

Kumaragupta from Naliasar- Sambhar discovered by Dr. Satya

Prakash offer some insight into the religious inclinations and

artistic taste of people. On the coin of Kumaragupta – from

Naliasar- Sambhar, a peacock as a vehicle of Swami – Kartikeya,

has been designed in a very beautiful manner. Six gold coins of

Gupta age were discovered from Bairh, a place situated near

Rairh in 1962. Some gold coins of Gupta age are also reported to

have been discovered from the areas of Jaipur, Ajmer and Mewar,

‘dmonastrating the important role the coins played in the

economic life of the people during the Gupta age’.

Useful information is also provided by several small hoards of

coins issued by various dynasties, tribes and rulers of

Rajasthan. Bairat has yielded 28 coins of Indo-Greek rulers, 16

of which belong to Menander. Excavation from Sambhar have

yielded many coins which include 6 punch – marked coins of

silver, 6 Indo – Sassanian copper coins. Rangamahal has provided

several Kushana coins, including some post-Kushana coins.

Kshatraps coins are reported from Nagari (Chittorgarh).

A significant number of coins were issued by the republican

tribes of Rajasthan. Prominent amongst them are the coins of the

Malava tribe. Thousands of copper coins issued by the Malavas

have been discovered, mainly from Nagar or Karkota Nagar (Tonk

District) and Rairh (Tonk District). The Malava coins from

Rajasthan are invariably of copper and a fairly large number of

them bear their tribal name. The Malava coins can be put in

three categories. The first category of coins bear the legend

Malavanam Jayah (i. e. victory to the Malavas). The other two

categories of coins consist of those coins which were discovered

in association with the Malava coins and resemble the latter in

fabric. The coins of second category bear no legend, while

those of the third bear enigmatic legends like Gajava, Haraya,

Jamaka, Magacha, Masapa, Pachha, Bhapamyana etc. the meaning of

these legends is not obvious to us.

|

|

|

|

|

Other Antiquities |

|

In the Vedas, the river Saraswati has been

eloquently and extensively applauded. It was, in fact, the

‘life-line’ of ancient Rajasthan Rigveda VI./49/7). The people

of Matsyas are also mentioned in the Rigveda. They have been

shown as residing near the banks of Saraswati in the Satapatha

Brahmana. The Salvas find mention in the Gopatha Brahmana, as a

pair Janapada alongwith the Matsyas had developed an extensive

kingdom with its capital located at Virata (present Bairat or

Viratanagara in the Jaipur District). The Pandavas are said to

have spent their period of exile at Virata with the help of the

Matsyas who were their allies. According to Mahabharata, the

Matsya Janapada was rich in the wealth of the cows and the

Matsyas were renowned for truth. The Mahabharata also refers to

the Salva country, with its capital at Salvapura, generally

identified with Alwar. The Malvas also find mention in the

Mahabharata as a tribe of great warriors which helped the

Kauravas in their battles against the Pandavas.

The Puranas contain some observations on the sacred places of

Rajasthan. Interestingly, the Skanda – Purana gives a list of

Indian states which includes some states of Rajasthan. These are

: Sakambhara Sapadalaksha; Mewar Sapadalaksha; Tomara

Sapadalaksha; Vaguri (Baged) 88,000; Virata (Bairat) 36,000; and

Bhadra 10,000.

The Chinese traveler, Yuan Chwang, makes certain references

related with Rajasthan. He mentions the place called Po-li-ye-ta-lo

which is identified with Virat or Bairat (Jaipur District).

According to him, “Po-li-ye-ta-lo was 14 or 15 Li or 2½ miles in

circuit’ – corresponding almost exactly with the size of the

ancient mound on which the present town is built. According to

Yuan Chwang, “The people of this city were brave and bold and

their king, who was of the Fei-she (Vaisya) race, was famous for

his courage and skill in war.” Yuan Chwang also mentions the

kingdom of Gurjara by the name Kiu-che-lo. According to him, it

was 5,000 Li in circuit. The capital of this kingdom was

Pi-lo-mo-lo, which is generally identified with modern Bhinmal.

Yuan Chwang says that “the king of this country was a Kshatriya

by birth, was a young man celebrated for his wisdom and valour,

and he was a profound believer in Buddhism, and a patron of

exceptional abilities.”

The period of 700-1200 A.D., in Rajasthan was of considerable

literary activity. The works composed by different authors

during this phase throw a flood of light on the political,

social economic and religious conditions of Rajasthan. |

|

|

|

|

Sources of the History and

Culture of Rajasthan (1200 – 1900 A.D.) |

|

The period c. 1200 – 1900 A.D. forms one of the

most interesting and inspiring chapters in the annals of Indian

History. But if one intends to study the connected accounts of

the political, socio-economic and cultural developments of

Rajasthan, he is faced with a paucity of material. Though a

comprehensive general view of the dynastic history of Rajput

states was provided by Col. Tod, Kaviraj Shyamal das and Dr.

Ojha, the study yet suffers from critical assessment of society

and other institutions. The study of these aspects calls for a

systematic analysis of source material. For a precise and

critical understanding of history our sources fall under the

following heads: (i) Archaeological sources; (ii) Documents and

Letters; (iii) Contemporary Literature; (iv) Travelers

Accounts; (v) Archival Records and; (vi) Illustrated Manuscripts

and Paintings. |

|

|

|

|

Archaeology |

|

Of all the sources

archaeology forms the primary source of our study. This branch

helps us to know much about important sites and monuments. The

mediaeval towns like Ajmer and Amber throw sufficient light on

the town planning and life in them. The details of village

economy can mainly be studied from the remains of the villages

which have been abandoned. Jawar is an instance of this kind.

The sites of urban regions afford a scope of study of

concentrations of population and possibilities of traffic and

trade with the neighboring states and land. The Military

History of the forts is an interesting subject of study.

Similarly, the study of the temples of Chittor, Amber, Ajmer and

other regions of Rajasthan enable us to gather information about

the evolution of architecture.

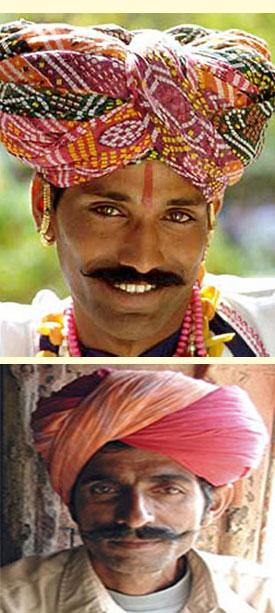

A detailed study of the sculptures leads us to elucidate the

social aspects of the life – the costumes, ornaments, dance,

musical instruments and pattern of living. The priceless

collections of several museums of Rajasthan and isolated

sculptures from various sites have their own tales to tell.

Though a large number of such pieces have met their premature

death, partly due to the ruthless activities of the invaders and

partly due to unsympathetic concern of public at large, the

remnants at our disposal offer clues to several problems for the

cultural history of our period. The images of Shiv, Parvati,

Yakshas, gods and goddesses, collected and preserved in the M.B.

College Museum, Udaipur, belonging to the 12th to 15th century,

depicts a large variety of garments and ornaments and throw

light on mediaeval cults of Rajasthan. A panel at Vela Kabra

temple, Chittor (15th century) depicts village life with a boy

playing a flute and a gathering to the Kirtistamba (Chittor)

depict dresses and ornaments of various classes of people of the

15th century. Kumbhalgarh helps us to determine the dresses of

aristocrats, the style of their moustaches and ornaments of 16th

century. The figures of the Memorial Stone of Gor Singh, Deobari,

V.S. 1736 depict a fight between a warrior anda lion. The carved

panels at Rajasamudra represent a dynamic impulse of art

depicting the costumes, beliefs and several aspects of social of

fights between the animals are highly informative regarding the

popular pastimes of a court in Rajasthan. The figures of Bhils

and Bhilnis, at the outer paner of Rishabhadeo temple, 18th

century, depict tribal life of the South – Western Rajasthan.

Of all the Archaeological sources and other sources, the

inscriptions which are found in abundance, in the form of

stone-inscriptions and copper-plate grants, form the primary

authority of the period of our study. Most of them are found in

temples, mosques and forts, reporting not only about the heroic

and pious deeds of their builders or donators but also

indicating the literary, linguistic, political, social,

religious and economic changes that took place subsequently in

Rajasthan. It is true that some of them record legendary

accounts, yet they, no doubt, serve as the real landmarks of

Rajasthan history. The language of the inscriptions of our

period is generally Sanskrit or Rajasthani. We also have a

number of inscriptions in Persian relating to the medieval

period from different parts of Rajasthan. Some of the

inscriptions are in the running Mahajani script, which is

difficult to read.

We have a number of copper plates also relating to our period of

study from different parts of Rajasthan. A copper plate grant of

1535 A.D., preserved in the old deposited records, Udaipur,

refers to Rani Karmavati’s performance of Jauhar along with

several other ladies of the royal household and of the notable

families of the period. A copper plate grant of V.S. 1669

records that Rana Karan Singh’s wife went to Dwarka and there

granted land to the Brahmanas. Several in the old deposited

records, udaipur of Bikaner give the classifications of land and

the rate of state demands. Similarly, a copper plate grant of

V.S. 1767 (1710 A.D.) refers to grant of jagir to the local

priest of Gaya, Varanasi and Hardwar at the time of immersing

the ashes in the sacred river Ganga. A Bikaner copper-plate

grant of 1816 A.D. is a specimen of the language bearing the

Punjabi mode of address to a dignity. |

|

|

|

|

Unpublished – Documents,

Letters etc. |

|

Next important source comprises of documents in Persian and

Rajasthani. There are several such collections in manuscripts,

preserved in various Government Departments or owned by private

individuals. These documents constitute very useful source of

our information. They are all unpublished. |

|

|

|

|

Contemporary Literature |

|

The production of literature in Persian, Sanskrit, Rajasthani

and Hindi has been a long tradition in our country. This kind of

literature covers several aspects – political, religious,

social, philosophical, astronomical, literary and scientific.

Though the main aim (leaving aside purely historical literature)

of its writing had been to enrich the special branch to which it

belonged, it also reflected richness in yielding historical

data.

Persian

If we turn up to Persian literature we find that much has been

written in this language, covering the history of the Sultans of

Delhi and the Mughal emperors. There are a couple of

autobiographies also written by the Mughal rulers themselves.

But as the main emphasis in this kind of literature is on its

accounts of the Sultans and the emperors, it is in vain to

expect from them much which is relevant for the history of

Rajasthan. However, due to the closer contact of the Rajput

princes with the Sultans and the Mughal emperors, we are in a

position to get the glimpses of the events relating to

Rajasthan.

Rajasthani Literature: Vat, Varta and Khyats

This kind of literature at times contains valuable material for

history. It is a class by itself and preserves traditions and

clan-accounts of the Rajpur families and ruling houses of

repute. The works belonging to this class contain material for

finding historical chronology. Some of them also help in

correcting genealogies of ruling dynasties. They also constitute

a valuable repository of information on the cultural history of

feudal families. |

|

|

|

|

Traveler's Accounts |

|

Quite a large number of European travelers visited India during

our period of study. Their accounts of the cities, court-lite

and general

condition of the country, though vivid, are full of the

interpretation and impression which is not free from personal

prejudices and idea of race superiority. Fortunately in the

general description of India given by the travelers, we trace

out here and there some references to Rajasthan which are useful

for our study of political, social and cultural life of the

state. However, in accepting their statements we have to observe

caution, as what they write is not wholly true and accurate.

William Finch in his Early Travels is in India gives a valuable

description of the outer wall and ditch of Bharatpu, prosperity

of Mewar and Amber. His account of Ajmer as a town and religious

place of the Muslims are very interesting. Similarly, Sir Thomas

Roe’s and Terry’s description of Ajmer and gifts from Jahangir

to Kunwar Karan are vivid and picturesque. Again Manrique Fray

Sebastian’s notices of the town of Jaisalmer, its people and

their local dances are highly informative. The accounts of

Tavernier and Betnier about eclipse, charity, sati system, Holi

festival, industrial activities and Indian poverty are of great

value. Manucchi’s references of the desert of Rajasthan, Ajmer

and Mewar are accurate. His accounts of villages and hills of

Mewat show his intimacy with the area. His observations on the

opium-eating habits of

the Rajputs are graphic. His references to the articles of

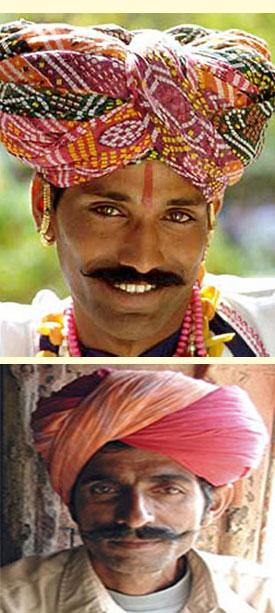

decoration of turban, festival of Holi and handicraft industries

of Rajasthan are of great use. Captain Mundy’s description of

the jungles of Bharatpur and the local dresses of the common

people of the town is graphic. Bishop Herber’s description of

Jaipur and Ajmer and his observations on festivals and local

customs are highly informative. |

|

|

|

|

Archival Records |

|

The princely states of Rajasthan had a historic past which

necessitated the maintaining of records of varied nature:

revenue, judiciary,

police, taxation etc. Obviously these records have a continuity

and throw sufficient light over the various aspects of life –

domestic, political, social and cultural. These records include

a large number of Bahis, Chopanayas, Haqiqats, Dasturs and the

like, prepared date and year wise under the supervision of the

officers of repute. They have been classified after the names of

the pre-merger states of Rajasthan. These records are

unpublished and written in Rajasthani dialects. A brief content

of some of these records will reveal that, being old and

authenticated, they are thoroughly reliable and throe a good

deal of light on some new aspects of the history of Rajasthan.

The Pattas or the revenue records (Bikaner) of our period are

the summaries of items of expenditure and income prepared year

wise. They preserve the mode and rate of revenue of the state.

The Sahar Lakha Bahi records the daily wages of masons and

labourers. The Kamthana Bahis give details of the construction

in the states. The Modi Khana Bahis and the Mahat – Talka Bahis

preserve the names of various office – holders like Patel,

Patwari, Chaudhari, Qanungo, tufedar, potdar, havaldar etc. The

Rokad Bahis refer to several local cesses. The Byava Bahis refer

to various rates of interest and private debts and credit

accounts of the States.

The archival records of Jodhpur consists of Bahis and Files. The

Byava Bahis, as for example, contain accounts of the rites and

ceremonies of royal marriages. The Haqiqat Bahis contain much

raw material for the political, administrative, social, and

cultural history of Marwar. The records pertaining to the

economic aspects have much to say about trade-routes, famine,

labour condition, export and import of the state. They are also

informative regarding festivals of Holi, Teej, Gangor, Dashera,

Diwali etc. the Havala Bahis refer to the units of

administration and the concerning office holders like hakims,

shiqdars, qanungos, thanayatolers, havaldars, chaudharies, etc.

The Hat Bahis preserves notes on the purchase made for the

imperial household, promotions and demotions of the officers and

other details of income from the parganas. The Portfolio Files

of Jodhpur contain original letters, drafts and notes addressed

to the administrators of and the rulers of the States. These

files make a valuable addition to the history of the inter-state

relations in Rajasthan.

The Jaipur Archives contain several kinds of records. The

Siyahah Hazurs supply a mine of information regarding the income

and expenditure of the state, the puchase made, variety of

articles manufactured etc. The Dastur Komvars contain names of

persons employed by the state and the gifts given to them on

several occasions. They also serve as service references. The

Tojees records refer to all items of income and expenditure

parganawise and datewise. There are also Tojees pertaining to

the various departments of the states. The Archival records of

Udaipur also have records like the Rojnamahs and Chopdas. The

Dargah files of Ajmer, for example, refer to the system of

education in the Dargah for the children of the Khadims,

donations made and religious services attended etc. The century

file No. (9) of Ajmer refers to 26 kinds of coins of different

values and weights in use in Rajasthan. |

|

|

|

|

Illustrated Manuscripts and

Paintings |

|

The Rajasthani paintings which are found in

huge collections at various museums, art galleries and private

collections of the state are

important landmark in his historical studies. They not only

represent the typical styles of different schools of the art,

beauty they also stand as testimony of the age to which they

belong. Right from the 12th to 18th century we come across

several paintings which present Rajasthani culture inits true

perspective, the account of which may be attempted through a few

illustrated manuscripts and paintings. The Kalkacharya Kathas

and the Kalpa Sutra manuscripts of private collections help us

to study the life of the aristocrats, their dresses and

ornaments from the 13th to 17th century. They also show the mode

of living, equipments of the household and other aspect of life.

Similarly the Bhavwat Purana MSS of Jodhpur and Udaipur may be

used with profit to study the pattern of the house of the

various classes of the people. The Ragini sets of Kota and

Jaipur museums paint ladies with dresses and ornaments peculiar

to their status. The Arsha Ramayan of the Saraswati Bhawan,

Udaipur depicts the scenes of the town life, village life and

life in hermitages. The illustrations of war and method of

fighting by the footmen and charioteers of that age. Moreover,

the manuscript is very important as regards the study of the

costumes and ornaments of the ladies and men of different

standard. |

|

|

|

|