|

|

|

Arts and Paintings of Rajasthan |

|

Arts

of Rajasthan

Rajasthan is among the richest states in the country as

far as the field of art and craft is concerned. Today,

various varieties and artistry can be seen in the

various forms of paintings. The two main forms of

paintings are the formal school of miniature paintings

that flourished in courts all over India and Deccan and

the folk traditions that resulted in a unique style of

the painting of Rajasthan. The history of Rajasthan also

revealed that the kings and their nobles were patrons of

art and crafts and they encouraged their craftsmen in

activities ranging from wood and marble carving to

weaving, pottery and painting. May be it was the result

of the war which sharpened the creative senses, artistic

skills which inspired the craftsmen of Rajasthan to

create the most opulent and richest of treasures. Stone,

clay, leather, wood, ivory, lac, glass, brass, silver,

gold and textiles |

|

|

|

were given

the most brilliant forms. For women there was infinite variety

- tie and dye fabrics, embroidered garments, enamel jewellery

inlayed with precious and semi-precious stones, leather jootis

etc.

Sculptural Art of Rajasthan

Just as Rajasthan is known for the fine quality of its

paintings, it is also known for its great body of sculptures.

The sculptural art is one of the most profuse forms of

decorative art in Rajasthan, particularly in the medieval

period and was lavished in palaces and forts, temples and stepwells, and the havelis or townhouses of the merchants and

traders. The main tools of the mason or sculptor were basic

and crude, and included the tanki or punch, the pahuri or

chisel, the hathora or hammer, and the barma or borer. The

main used these simple elements, and followed the texts

designed especially for his use (Shipashastra and Manasara) to

build the perfect jharokha or arch or pillar. The texts are

very exhaustive on details and the individual expression of

creativity is permitted. There are two ways to examine the

issue of the sculptor’s art as an architectural embellishment,

and as stand-alone work. The stand alone art was very little

used in Rajasthan, and figures were carved either for

enshrining in temples, or sculpture was part of the great

design of architecture. |

|

|

|

Religious icons were always carved from marble and the

Makrana marble mines supply the marble for centuries.

Even today, in most of the shrines in India, the

religious images are carved in Jaipur where religious

iconography has developed into a fine art. But Jaipur is

merely a centre for creating marble images. For sheer

details, there is nothing to beat the excessive marble

sculpturing developed by the Jains at their temples.

Most of the Jain temples have large statues of their

trithankaras enshrined in the sanctum. The best examples

of Jain temples in Rajasthan are in Mount Abu and

Ranakpur. Mount Abu’s Dilwara temples contains four

principal shrines and are housed together. These temples

were built between the 11th and 12th centuries and used

all the administrative skills. The Ranakpur Jain temples

are one of the most beautiful temples raised by the

Jains in India. At the heart of the complex is the

temple of Adinath, one of the largest, most extensive,

and characterized by its excess and profusion of

sculpture. The temple has 29 halls supported by 1444

pillars. Not one of these pillars are alike in one way

or other and entirely sculptured with arabesques,

motifs, and statues.

Jain

temple architecture is characterized by its

|

|

|

|

profusion of

sculpturing. The stone is moulded, chiseled, scooped

out, and developed so that each grain becomes a part of the

grand design of the temple. Nor is the work limited to a

similar repetition: pillars can be carved differently so there

is no one that is similar to another; each of these is alive

with images of gods and goddesses, musicians and dancers, and

there are architectural embellishments of such amazing

fluidity that it is impossible to disassociate architecture

from sculpture. The Jains also provided the basis for the

flowering of sculptured architecture in Jaisalmer. The Jains

were very rich and lived in the havelis, which were more royal

than the king's palace. They used sandstone in the havelis.

Some of the famous havelis in Jaisalmer are Nathmalji ki

Haveli, Patwon ki Haveli and Salim Singh’s Haveli. These

havelis were built in the 18th and 19th centuries by the

Muslim masons. These masons developed a body of sculptued

architecture that was not repeated elsewhere and also used the

expression, so that each mansion was like a textbook on the

subject. Fluted columns, balconies, arches, domes, jharokhas,

eaves, brackets and cupolas were carved very differently. Two

stone mason brothers were so adapted to their task that their

names, Hathu and Lalla, are still recorded in the annuals of

Indian art. While statuary as a part of architecture, and

geometrical and floral expressions, found a reflection in all

part of Rajasthan, the sculptors of Barmer, found creative

expression in their rich arabesques on the red sandstone.

Barmer continued to remain, one of the prime centres for

sandstone carving in the state.

Paintings of Rajasthan

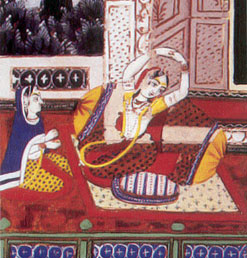

Various Muslim artists worked in the Rajput courts, and Hindu

artists worked in the Mughal court. The Chittorgarh court also

offered employment to the Muslim painter and had a seminal

school in the 16th century from where a collection of Gita

Govinda paintings may have originated. Due to this, the Mewar

school become one of the most important schools in the state.

The Mughal artists of Delhi were welcomed by the rulers of

Rajasthan due to the decline of their patronage in the Mughal

court. As a result of it the Rajasthani school of paintings,

murals and miniatures came into existence in the 16th century.

In Rajasthan, from 16th to the 18th century, about seven

styles of painting developed over a period of time, and in

different kingdoms. The miniature paintings also flourished

before the establishment of the 16th century Mughal studios,

particularly as illustrations for manuscripts, and Akbar also

hired various court painters from Hindu kingdoms in North

India. The miniature painting is a portfolio painting that

uses techniques similar to wall paintings, cloth paintings or

manuscript illustrations from which it may have evolved. These

paintings are painted on a paper that has been specially

treated, and uses vegetable and mineral colours. Some of the

examples of the miniature paintings can be seen in the Mughal

and Rajasthani styles that existed in the 16th century. The

Mughals miniature paintings were restricted to court scenes

and portraits of the emperors and the rulers like Akbar,

Jahangir and Shah Jahan and also derived inspiration from

them. While, the Rajasthani school of miniatures was

characterised by a revival based on its increasing contact

with the Mughal Durbar. Various strong colours, bold

compositions, the range of hues almost passionate in their

intensity, and in their response to the life of the people,

ornamental depiction of nature and accentuated human forms

were used in the Rajasthan miniatures that reflect the Rajput

culture. |

|

|

|

The

main difference in the paintings was in the way the

painter looked at the countryside, hills, shrubs, forts,

gardens and sand dunes. The miniature paintings were

made on the variety of subjects like the kings,

religious and secular. But, their main subject was the

description of the Krishna Leela. In the Gita Govinda,

the miniature paintings also became a lyrical symbol

with swaying lotuses, meandering streams, and trees

suggesting the intimate passions of lovers. The epics

like the Ramayana and Mahabharata formed as the base for

religious works of art. Later, shades of royal lifestyle

came to be seen on the canvas of the painters, and

ranged from hunting scenes to ladies playing chess, or

polo.

Earlier, the finest miniatures used to be painted on

ivory, but it is now banned in India. The same artists

also tried to bring the same effect on marble but

|

|

|

|

achieved very

less success. The painting on marble looks like the gesso work

from Bikaner that can be seen on the camel hide. Most of the

artists also used walls to create paintings, and a profusion

of work can be seen in the palaces of most of the kingdoms

where every walls and ceilings are lavished with scenes from

the Krishna Leela, or the exploits of Lord Rama, or the court

scenes and portraits of rulers. In aristocratic homes, the

secular and religious scenes were presented. Frescoes

paintings can be seen on the walls of palaces at Jaipur,

Udaipur, Bikaner and Jodhpur. Most of these paintings have the

themes of the Krishna stories, Raslila and Hindu religious

subjects.

Today, miniatures are turned out in almost

every studios that have been especially developed to help in

the tourist souvenir trade. These studios can be seen in

Jaipur, Udaipur and Kishangarh. Even now, the talent is

available in plenty, but the best artists rarely finds their

way in the open market. They are commissioned directly, and

their work can be seen as the collections, or used to

illustrate prestigious art books. Most of these works are

copies of earlier paintings, and original subjects are very

hard to find.

Folk Styles of Painting

While the formal school of miniatures were patronised by the

royal families and the aristocracy, the humbler settlements

patronised the humble forms of art and were very expressive.

The folk paintings used fabric as the material and emerged in

two styles. These two folk styles of painting are Phads and

Pichwais.

Phads

Phads are scroll-like paintings on a giant canvas that were

used by the Bhopa ministers to recount the legends of Pabuji

Ramdeo of the Rabari tribe, and his black mare. The tales are

painted in flaming orange, red and black colour in comic-strip

fashion. There is very little detailing and the expressive use

of the outline of human figures and the sketchy filling of the

background creates a lively tapestry. |

|

|

|

Pichwais

Pichwais are decorative curtain cloths used as a background

for religious images in a shrine. These can be brocaded block

printed, embroidered, or worked in gold threads. In the

simplest form, they can be secular in nature, and are painted

in huge quantities for sale to tourists. The Pichwai developed

when the Vallabhaichari sect created 24 iconographic rendering

as a background for the Krishna image at Nathdwara. Each of

these images were linked with a particular festival or

celebration. While images from Nathdwara are instantly

recognizable in the way Krishna is painted, and in the

decorative element that embellishes the cloth, the traditional

pichwai consist of starched, handspun cloth painted |

|

|

with vegetable and mineral colours like

cochineal, indigo, lapiz and orpiment. Nowadays, the fabric

colours are used. The format of the pichwai is static, where

even the natural elements appear ‘frozen’. The elements like

the sun, moon, stars, or even lighting appeared in the

painting.

Royal Styles of Painting

The Rajasthani miniature painting evolved various styles that

can be seen in the different kingdoms where it found

patronage. The miniature paintings were initially used as

illustrations for texts, and later evolved as portfolios of

the life and times of their royal patrons. In Rajasthan, there

are seven distinctive styles of Rajput paintings, and later

they evolved in the seven states which are Bikaner, Bundi and

Kota, Kishangarh, Jaipur, Mewar.

Bikaner:

One of the finest schools of miniatures was developed in

Bikaner. These paintings existed from 1600 onwards and show a

marked Mughal influence. In fact, the local style kept pace

with the painters in the Mughal court, and were not

expressive, while the Bikaneri artist tended to be more

expressive. The delicate sub colours were used and there was a

delicacy in the portrayal of human and vegetation forms. The

Mughal and Bikaneri miniatures were sometimes mistaken with

each other, as the pleasant background, colourscapes and the

foliage (as if to make up for the desert conditions), were

very luxuriant.

Bundi and Kota:

The Bundi and Kota school developed two different identities,

but have the same common identities. The Mughal intervention

blended the two traditions of illustrating court scenes. The

human figures appeared to have a haunting appearance, and were

not marked by formal austerity. The early works were the

commissions for illustrating traditional texts like Ragamala

and Rasikapriya. The hunting scenes captured the fancy of the

artist. As the school developed, it evolved into an entire

school of its own from 1700 onwards. The paintings have a

green tint and idealized the landscape and forestscape. The

feminine grace in group of young women leading to works is

very colourful, and creatively handled in the paintings. In

the Bundi school, the background usually consists of thick

foliage, with a sky over laden with clouds and illuminated by

the light of the setting sun. The architectural background is

equally impressive, with palaces and apartments depicted in

fine details. There is a lyrical expression of love that can

be seen in the paintings, and ornamental backgrounds. The same

style evolved in Kota, but it developed its own expression in

a similar and independent form. |

|

|

|

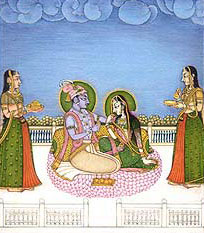

Kishangarh:

The Kishangarh artists were very brilliant and there is

nothing that matches their brilliance that lasted only

for a short while. Kishangarh was a Rathore kingdom, and

their early work was similar to that of the Marwar. A

more advanced style later replaced this in the first

quarter of the 18th century, and reached a point of

perfection under the rule of Savant Singh, the heir to

the throne of Kishangarh who finally abdicated in favour

of his son and chose to live a hermit’s life in

Brindavan. Under Savant Singh’s rule, the Nihal Chand,

one of the finest painters of the period and a school of

paintings dealing with Krishna and his lady love, Radha,

emerged. It is believed that the figures of Krishna were

modeled on Savant Singh , and those |

|

|

|

of Radha were

modeled on his mistress, known as Bani Thani. The portraits of

Bani Thani are among the most attractive miniatures in India,

and she obviously inspired Nihal Chand to cast her as Radha in

his Ras Leela scenes. The Kishangarh figures are exceptionally

attractive, and show a refined delicacy. The backgrounds

shared the elaborate style of Mughal paintings, together with

the use of the evening light, but the artists used a greater

expression of creative freedom. The Kishangarh paintings are

among the finest body of arts that were expressed in a canvas

of such elaborate colours.

Jaipur:

The Jaipur school of miniatures, which is still active, was

also the most formal school of miniatures. It was a kin to the

Mughal in the backgrounds, and in the court settings, but its

subjects were more secular. Of all the schools in Rajasthan,

Jaipur’s use of colours is the most understated. The depiction

of the human figure, by the 18th century, had been perfected.

The faces are accentuated, the eyes are large and curving, the

turbans are worn high, and while they sit or stand or ride,

the men are shown with a sense of vibrant energy. Even

paintings showing rulers practicing religious rituals are not

devoid of this quality of vibrancy. The background is more

characteristic with thick, rich decorative leaves of trees,

and skies are

enriched with thick, rolling clouds. Aniline colours too are

an important feature.

Mewar:

The Mewar school of painting is one of the largest school of

miniature paintings in Rajasthan. These miniature paintings

were found in Udaipur, from the 17th to 19th century. The main

theme of these paintings was the traditional text that ranges

from the Ragamala, Nayika-bhada and Krishna Leela to the

Ramayana and the Bhagvata Purana. The scenes from the Krishan

Leela came to be known for their amorous quality. One of the

first definitive sets of Ragamala paintings of 1605, and

executed by painter Nasiruddin, can be still seen in the

collections at Udaipur. The Mewar school is known for its

strong colours and decorative designs. The landscape has been

emphasized so that the human figures tend to integrate with

it. The decorative features were further accentuated with

Mughal cross fertilization when a mosaic-like, decorative

character evolved, due to foliage. Later, lifestyle portraits

were developed in the Sisodia school, replacing nature with

the background of the palaces of the Ranas. |

|

|

|

|

|